Introduction

This article is part of series on the High Quality Instructional Materials (HQIM) Movement being embraced by many states across the nation. It provides a brief policy view of the last 40 years and explores how HQIM may fix the damage done by the 1983 report “A Nation At Risk.” Our series on HQIM also looks at:

- The origins of the HQIM movement

- How certain states are implementing HQIM

- EdReports.org: Who, What, and When

- Perfect Timing: HQIM and the Rise of AI

Dick and Jane Taught 3 Generations to Read

When I was in grade school in NYC during the 1970s, I was actually issued a textbook that my mother had used when she’d been in the same school 25 years earlier. How did I know? There was a sticker on the inside cover where the names of students to whom the book had been issued were written.

Now, you might be thinking “was NYC out of money?? Why did these kids not have newer books??” Yes, NYC was headed for a financial crisis, but that would come later. We didn’t have new books because we didn’t need them.

During the 1940s – 1970s, as many as 80% of American schools used the Dick and Jane textbooks to teach reading. My parents and siblings, far-flung aunts, uncles, and cousins were all taught to read with the same stories and illustrations. And we all looked forward to Fridays, too, because that’s when the new Weekly Reader came out. Even my grandmother received that little newspaper back in her day. Across three generations, we had similar experiences in our beloved neighborhood schools.

For a good portion of the 20th century, Americans had what amounted to a common curriculum in Reading. Literacy rates in adults were reported as high– 86%, at least according to the Census Department. All was well, right? That’s what we thought… . When the newly authorized Department of Education opened in 1980, what we thought we knew about the quality of education in the United States was soon to be upended.

The Federal Department of Education Is Created

The federal Department of Education grew out of the passage of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965, part of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “War on Poverty.” To this day, the act (under many aliases, e.g. NCLB) continues to provide federal funding for primary and secondary education, with monies allocated for professional development, instructional materials, resources to support educational programs, and the promotion of parental involvement. It emphasizes equal access to education, aiming to narrow the achievement gaps between students by supporting schools with children from impoverished families, aka Title I schools.

In the ensuing years, federal investments in K-12 education grew but they were scattered across agencies such as Agriculture, Interior, and Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW). It became abundantly clear that a centralized agency was necessary. The federal Department of Education was created by the Department of Education Organization Act, which was signed into law by President Jimmy Carter on October 17, 1979 and began operations on May 4, 1980.

Congressional Authorization of the Dept of ED

Congress authorized the agency to operate and oversee federal assistance to education, collect data on US schools, and enforce federal educational laws regarding privacy and civil rights. Its mission was to:

- ensure access to equal educational opportunities for every individual.

- supplement and complement the efforts of states, local school systems, and other instrumentalities of the states, the private sector, public and private nonprofit educational research institutions, community-based organizations, parents, and students to improve the quality of education.

- promote improvements in the quality and usefulness of education through federally supported research, evaluation, and sharing of information.

- streamline the processes, procedures, and administrative structures for federal education programs and the dispersal of funds.

- increase the accountability of federal education programs to the President, the Congress, and the public.

While the Department of Education went about setting up shop, presidential administrations changed. Reagan was now president. He appointed Terrell Bell as the first Secretary of Education. President Reagan wanted to get rid of the new agency and Bell did not; he’d just moved to DC and wasn’t interested in leaving so quickly. Being politically savvy, he formed a bipartisan commission to look at the quality of education in the US, knowing that it would be a bombshell. How did he know this? He manipulated the data that the Commission was given to work with.

An Orchestrated Smear Campaign: A Nation At Risk

The first time the general public took notice of the new agency was in 1983 when the DoE released the Commission’s devastating report, “A Nation at Risk.” The most famous quote from the report was cited by the media countless times:

“the educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation and a People… If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might well have viewed it as an act of war.” (See the original report here.)

Politicians, including Reagan, loved that there was a new scapegoat, a political bogeyman taking shape in the voters’ minds. They used it to foment dissatisfaction with public education, lower funding for ESEA, and distract voters from their very real inflationary woes back then.

My neighborhood was the Bay Ridge area of Brooklyn, NY. It was a diverse area that was home to mostly second, and third generation immigrant families from Europe and the Middle East. Our fathers were a mix of professional, service, and trades men. Most women were homemakers and there weren’t any people of color that I recall. It was a mostly Eurocentric middle class area. So when “A Nation at Risk” was released by the Department of Education in 1983, it shocked the comfy American Dream Seekers of Bay Ridge– and thousands of similar communities across the country. We were told that we could not trust our own experiences in our neighborhood schools nor believe our own eyes as to their quality because an official report proved us wrong.

The nation was aghast. We willingly marched down a patriotic path– NOT the targeted ESEA path of fixing failing neighborhood schools in high poverty or predominantly minority areas as envisioned by President Johnson. No, no– we were preserving America’s economic dominance in the world, a favorite theme of President Reagan’s administration. ALL schools had to be fixed, even though most were doing just fine.

Sandia Report Seeks to Right the Wrongs of A Nation At Risk

One of the main claims of A Nation at Risk was that US scores on SATs had dropped and, if the trend continued, we would no longer be globally competitive. America would fall behind. That was the national wake up call our country received, so potent a narrative that it persists to this day. However, it was wrong, as in not true, false, and fake.

The Sandia Report, commissioned during the President George H. W. Bush administration proved that our competitiveness was actually not at risk; the SAT test score data on which the 1983 report was based had not been properly disaggregated. The Commission that produced the report was looking at test scores of all college applicants between 1960 and 1980. Applicants were mostly white men in the 1960s. Yet after the enactment of the ESEA, more women and people of color were taking the college entrance exam. When the achievement line trended slightly downward in the 1970s, the Commission drew an invalid conclusion– comparing apples to oranges, if you will. There were no statisticians on the Commission.

However, it was indeed statisticians who had prepared the data for the Commission to look at back in 1981. Had they forgotten to break out the data based on demographics, or were they just following orders and deliberately manipulating the data to make it look bad? If they’d extracted the white guys’ scores only throughout the time period, the data would have shown highly competitive SAT scores: apples to apples. And perhaps the Commission might have even praised the significant progress made by people of color and women in applying to college. (Their participation was largely thanks to funding under the ESEA.)

Sandia Report is Buried

Alas, the truth revealed in 1990 was not potent enough to put the 1983 false narrative of failing schools to rest. Instead, the bureaucrats of the day led by then Secretary of Education Margaret Spellings buried the report and continued to try and “fix” a system that was working for 75% of the population. Do not misunderstand me: schools in impoverished areas (which were predominantly Black, Hispanic, and Native American) desperately needed help, but not for the reasons put forth in A Nation At Risk.

The irony of it all is that the Commission actually promoted some excellent reforms that would have supercharged education across the socioeconomic landscape. Unfortunately, over the next two decades, only two of their 38 recommendations ever gained traction: higher HS graduation requirements and the need for (uniform) academic standards. What they’re remembered for is starting a war on one of America’s best ideas: public education for all.

A Nation At Risk Spawned 40 Years of Bad Press

Over the last 40 years, the pernicious false narrative combined with decades of low funding and a byzantine array of laws and policies has transformed our perception of public schools. No longer are they perceived as respected community institutions with committed teachers; now they are thought of as expensive bureaucratic failures with bad teachers to blame. It’s become a “self-fulfilling prophecy” as a result.

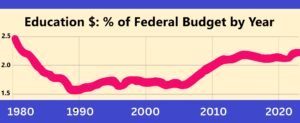

The Reagan Administration gutted funding for education by 40% through the 1980s. Three subsequent administrations brought about slight increases. Today, ESEA funding is still 15% lower than in 1980. More Title I funding for students below the federal poverty line and competitive grant programs have happened under Bush, Jr., Obama, and Biden. Yet public schools continue to struggle under the weight of over 40 years of malificence and misguided reforms. Many states have added insult to injury by enacting draconian laws that hamstring school administrators, drive teachers out of the profession, and perpetuate community dissatisfaction.

Fortunately for America’s youth, educators have proven to be laudably resilient despite the politically calculated destruction of the public’s trust. They have continued to work towards the primary goal of educational attainment for all as originally envisioned by the ESEA 60 years ago. They do this despite a journey more harrowing than what Gulliver encountered in his travels.

Can the HQIM Movement Change the Narrative?

Is there hope on the horizon? Possibly. It is educators, not politicians nor policymakers, who started the High Quality Instructional Materials (HQIM) movement. It is gaining speed today as state departments of education and legislatures begin to mandate HQIM use in schools.

What is HQIM?

The HQIM movement is a refreshing, educator-led approach to educational attainment for all. It emphasizes the importance of providing teachers across a state or district with the same high-quality, research-based instructional materials aligned with academic standards. This movement recognizes that when teachers have access to the best possible resources, they can provide more effective instruction and better support student learning. And if all students are learning from the same set of curriculum materials, apples-to-apples comparisons will finally be possible.

High-quality instructional materials are designed to be engaging, culturally responsive, and accessible to all students, including those with diverse learning needs. Their use should help to ensure that all students, regardless of their background or circumstances, have the opportunity to succeed academically.

The HQIM movement also promotes professional development for teachers, helping them to effectively implement these materials in their classrooms. By investing in teachers’ growth and development, the movement aims to improve the overall quality of education and student outcomes.

The Healing Potential of HQIM

Looking back at how common resources like the Dick and Jane textbooks and the Weekly Reader were successfully used across generations in my own Bay Ridge neighborhood, I am optimistic that a common curriculum can begin to reverse the narrative. Perhaps we can look forward to an era where common educational resources and shared expectations uplift ALL of our schools– and especially our heroic teachers.

The HQIM movement offers a hopeful antidote to the fake reform movements of the past four decades. By once again empowering educators with high-quality resources and professional development, maybe we can focus on student learning and fulfill the original promise of the ESEA: equal educational opportunities for every child. HQIM has the potential to rebuild trust in schools, empower teachers, and reclaim the public’s confidence.

Let’s hope it does so. Education is considered essential for a democracy to exist. Even more essential are the teachers who instruct our children. They provide the true foundation of our American way of life and we owe them our respect. — Laura Bresko, CEO Classwork.com